Sophie: Let’s talk survey technicalities! What sort of sampling and stratification did the 2010 IFS use?

Mary: The IFS used the same sampling frame since 1975: a random sample of birth registrations from August to October 2010. For 2010, we wanted to make sure that we obtained good information about groups with historically low response rates. The most deprived groups often have low survey response rates as well as low breastfeeding rates so we oversampled to get better representation.

Sophie: How were participants recruited, reminded and what was the response rate?

Mary: Some 30,000 mothers were contacted by post timed to coincide with their new baby being a few weeks old. Mothers who completed this first round were sent another round at about four to six months and then another around eight to ten months. 10,000 mothers completed all three rounds of the survey.

Sophie: What kind of survey was it?

Mary: It was historically a long, comprehensive postal questionnaire with 70-80 questions. The length will inevitably have had implications for women’s willingness or ability to participate. In 2010, we added the option of a websurvey as well.

Sophie: What did it ask participants? Apart from are you breastfeeding your baby?

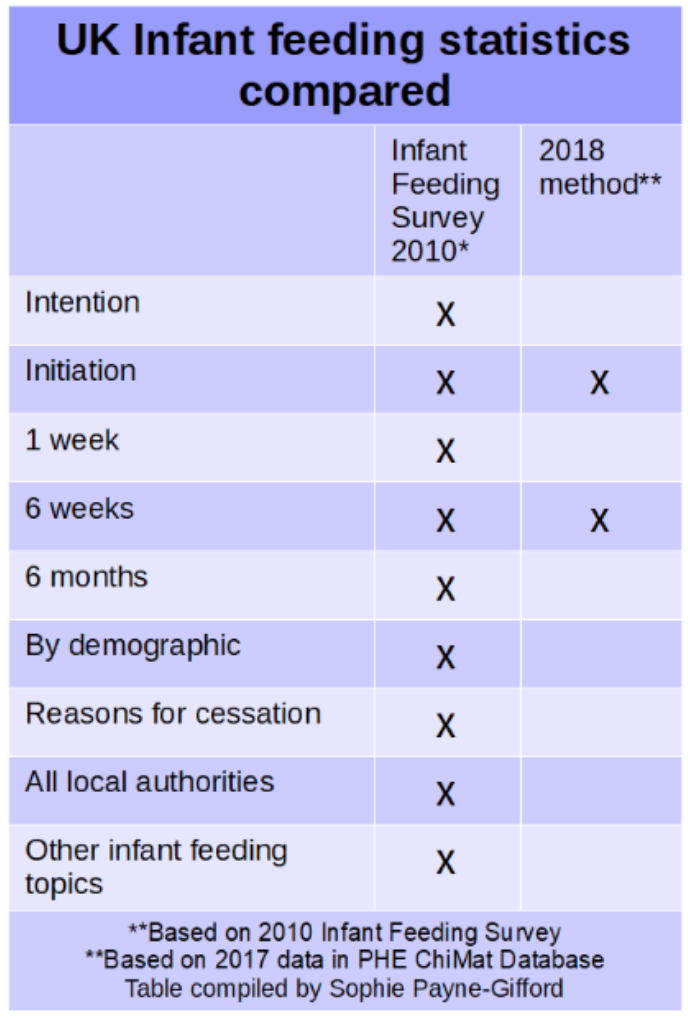

Mary: Before asking participants how they were feeding their infants, it asked participants if that’s how they intended to feed them. It then asked them if breastfeeding was initiated at birth, if it was still ongoing at 6-8 weeks after birth and then again at 6 months. If respondents had started breastfeeding and subsequently stopped, it also asked why. It also asked participants about feeding solids, formula, and other fluids to their babies.

Sophie: Do the results vary by demographic, or any other variable?

Mary: Yes. Put simply, poor, white, teenage mothers were least likely to initiate breastfeeding at all.

Women over 30 years old, those who continued education after 18 years old, and those who were from Black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups were most likely to breastfeed.

Sophie: Do you remember how much it cost to run it and how many people were involved in the endeavour?

Mary: I think it was around £600K. The survey company IFF handled all the logistics – they had a small core team with additional help at key stages, to manage the posting of the surveys and the data input for example. I was the academic collaborator.

Sophie: Do you have any comments about England’s decision to discontinue the IFS?

Mary: It was a policy decision, presumably related to political priorities. The official reason given was funding constraints – it was the early years of austerity - but Scotland decided it was important enough that it ran it on its own in 2016.

Sophie: What are the current arrangements for collecting breastfeeding stats?

Mary: The Infant Feeding Survey was not run in 2015 in England (nor Wales nor Northern Ireland). So what has been collected in England from 2015 is:

a) Hospital indicators: rates of breastfeeding initiation at birth reported by local authority;

b) Public Health England: breastfeeding rates at 6-8 weeks reported by Health Visitors, again reported by local authority;

c) Quality Care Commission maternity survey also collects some info about feeding experiences

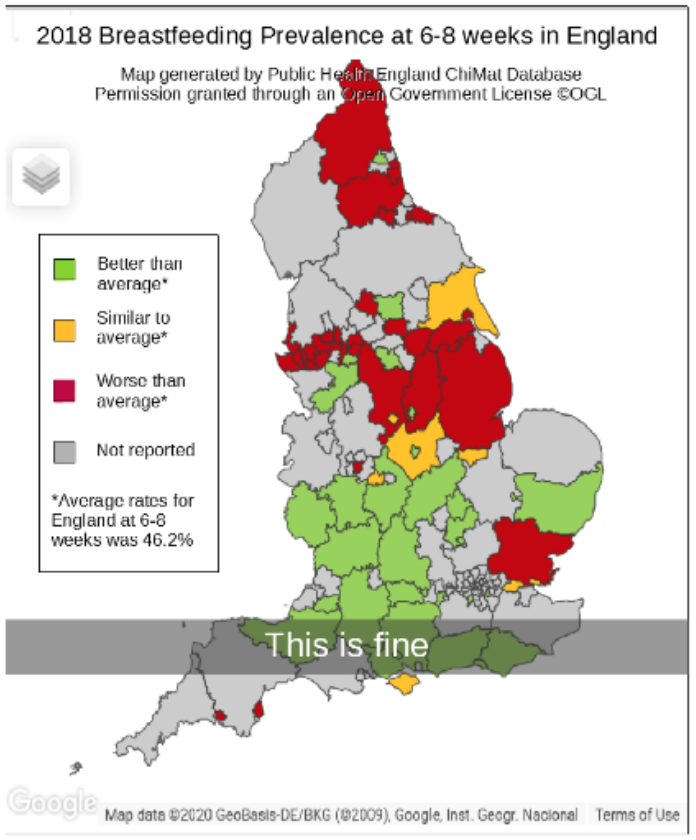

But information about rates beyond that is not collected. For me, this data collection approach is fundamentally missing mother’s voices, their experiences. It also means public health policy decisions have to rely on short-term and less comprehensive information. Many local authorities are not reporting their breastfeeding rates, presumably due to over-stretched maternity and health visiting services not having the time to collate their statistics.

Sophie: Yes, this is quite apparent in the public data release [statistical release spreadsheet available here]. Here’s the national picture (map produced from the Child and Maternal Health database ) 1 .

Mary: The current method is a blunt instrument. It is hard to analyse on deprivation demographics. Also, we’re not getting a view across the four countries (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). Infant Feeding Policies vary by country and before we could compare outcomes. We’re now really in the dark for three out of four countries.

Sophie: I can also tell you that breastfeeding groups aren't using the current reporting data. They don’t trust it. They don’t understand how it’s been collected or whether it’s accurate. They also can’t imagine that our already busy midwives and health visitors have time to collate breastfeeding statistics. The statistic on intention to breastfeed (75% in the 2010 IFS) is important to breastfeeding groups but is also no longer collected.

---- A few weeks later ------

I showed the the statistical release spreadsheet to Kate Johnson, a quantitatively-minded animal scientist (veterinary surgeon to be precise). Being more familiar with such spreadsheets, she had a poke around (the technical term), clicked on some cells and figured out that the grey areas had not reached a certain percentage of births or 6-8 week appointments reporting rates. She concluded that this reporting method is a an attempted census of births and 6-8 week appointments. Surely more returns is better?

Kate: In trying to calculate statistics, whether it's a population of sheep or breastfeeding mothers, non-response is important. We obviously don’t know anything about those people (or animals) that have not been surveyed. In this case, it is whether they are bf or not and if we make assumptions either way, any stat reported is unreliable. When you run a stratified survey you make sure you get responses from a population that represents your target population. Just like Mary explained above - the proper infant feeding survey targeted groups that might not reply. By running a representative survey your answers represent the population as a whole.

When you try to collect everyone’s data some people don’t reply. And those people aren’t representative of the whole. People at a social or economic disadvantage, people who don’t speak English, people who don’t access Health Visitors. Your missing data is biased and not random. The data you get will not necessarily be similar to the regions where you couldn’t get

the data.

However, if you aren’t trying to sample everyone you can resample, i.e get more responses because there are people (or animals) you haven’t surveyed. And you can resample the populations that you particularly want to know about. The statistical theory is the same.

Censuses are great when there is adequate coverage, but that can be difficult to achieve without resources. I’d choose a survey, with a carefully chosen sample, over a census any day with its inevitable missing responses.

Summary

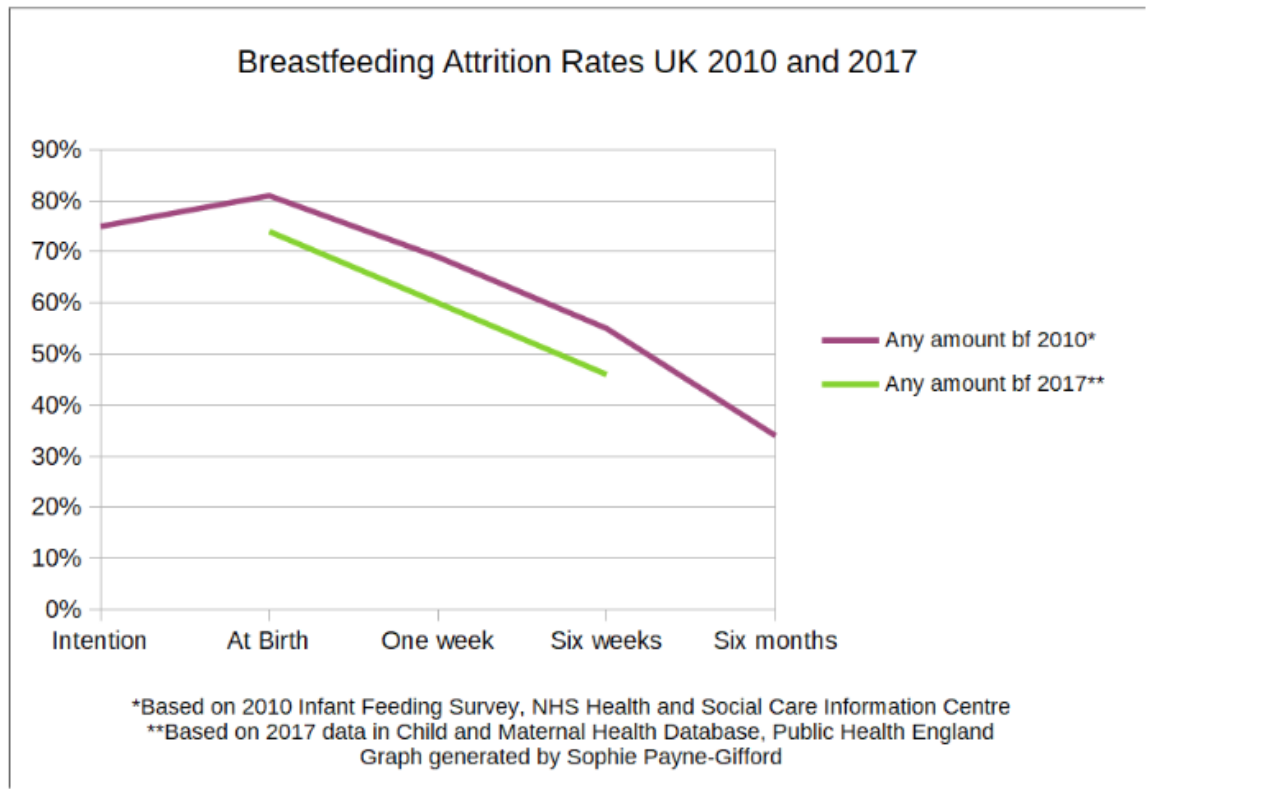

It is possible to plot the two data points available under the current data collection system (see graph below). It suggests breastfeeding initiation rates may have declined from 80% in 2010 to 75% in 2017 and the attrition rate remains bleak. However, it’s hard to know whether the 2017 data suffers from response bias, i.e is an artefact of those local authorities with the resources to collect and collate this information.

In conclusion, the current method of collecting and reporting bf stats is pretty lousy. This table sums it up:

Author Bios

Sophie Payne-Gifford is a senior research fellow at the University of Hertfordshire working on sustainable food systems. She's mostly a qualitative researcher but thinks surveys are pretty fun.

Mary Renfrew is a semi-retired professor of Mother and Infant Health. Retired in that she's (mostly) retired from her position at the University of Dundee. 'Semi' in that she's still working on things....

Kate Johnson is Sophie's job share the University of Hertfordshire. She's also a veterinary surgeon and lecturer at the University of Reading. Seem a little left field for the *Social* Research Association? She is a specialist in dairy heifer calves - and it turns out all baby mammals need milk and it is up to people whether dairy calves get it or not.

Footnote:

1. The Child and Maternal Health database also has loads of other data and views available including maternal smoking, childhood caries, A&E admissions and more.